The easy part was finding Hoke Secrest guilty of murder. The court case provided overwhelming evidence that he married then murdered widow Maggie Stephenson and her four-year-old daughter, Minnie in March of 1877, likely for the land Maggie inherited from her late husband. It was called “The Hickory Murder,” the first sensational crime in the young town’s history.

Secrest’s defense lawyers offered testimony that Maggie had been seen alive well after the murder was supposed to have taken place, at Christmas, no it was the fall of 1877. On the stand, the witness got tangled up, rendering the testimony unreliable. When Secrest returned to Union County without his bride and stepdaughter one witness accused him of the deed for which he was later convicted. Another told how he wanted a letter written as if from the hand of Maggie denying they she married Hoke but sold him her land while she intended to head west for a new start. A signed marriage license proved Secrest sought to weave a web of deception.

But that was not the end of Hoke Secrest. His distraught family sought a retrial. The second time, the defense claimed he was not guilty by reason of insanity. Convicted again, his life was spared. Instead of swinging from a hangman’s rope (the first sentence) he was confined to the state mental asylum in Morganton (Broughton) for life.

From there the odyssey begins a new chapter. After several attempts, Secrest escaped. He fled to South Carolina and lived under the assumed name of B.E. Gray. However, his temper followed him. Again, he married a widow who owned a farm in Spartanburg County. To help with the chores, the couple adopted two orphan boys. When Secrest/Gray beat one, almost mortally, he was incarcerated again, this time in the Palmetto State.

While serving 20 years at the penitentiary, someone recognized him as Hoke Secrest. “He immediately began to feign insanity, and nothing could be done with him until he had been severely whipped, when his reason returned as speedily as it had departed,” was how one account described the incriminating incident.

Brought back to Morganton, the state hospital would not accept him, so he was jailed and put on trial for a fourth time, the last one held in Rutherfordton. He was now widely known as the “wife and child murderer” although he quipped to reporters that he couldn’t even remember marrying Maggie Stephenson, much less murdering her. This time he got 20 years for manslaughter.

Twice, mobs formed and tried to lynch him, first after he was brought back to Morganton and when passing through his hometown of Monroe on his way to the state prison farm in Anson County. In each case, a heavy guard prevented folks from taking justice into their own hands.

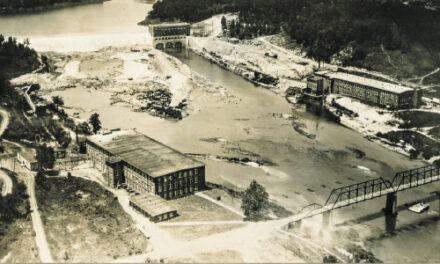

Three years into his latest sentence, he made another jailbreak. Evidently, he could find a way out, he just couldn’t stay out. Caught again, Hoke Secrest returned to prison. He died at Caledonia State Farm in April of 1902 at the age of 50.

The press lamented over the fact that the bones of Maggie and Minnie Stephenson were never buried. They were used for evidence in the various trials that aimed to put away Secrest. Recounting the journey, one report said, “when murdered they (the bones) were ruthlessly cast into a shallow hole from whence they were dragged by dogs and wild animals. Then taken to court, they were bandied about from pillar to post for nearly 20 years till the last trial of Secrest in 1895, after which what few scraps that remained of them were sent to the clerk of the court in Monroe to be turned over to relatives. They have never been taken from his office and today (as of 1897) be there in a small rough box under a table. Verily… (s)he who is born to go unburied will never sleep peacefully in a grave.”

Photo: Caldonia State Prison Farm, where Hoke Secrest spent his final years.