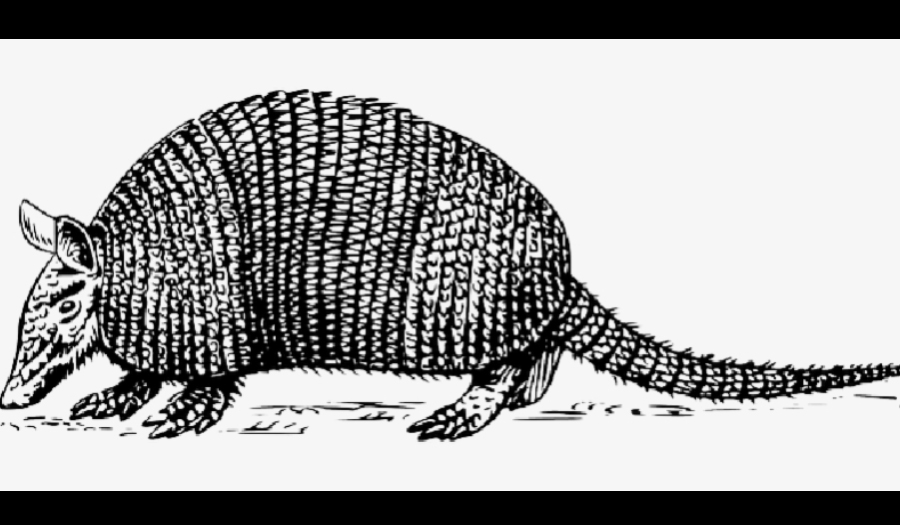

Just after New Year’s Day in 1923, a rampage near Hickory came to an end. Before it was over a crime spree swept the countryside north and west of town. Farmers (and there were still a lot of them in those days) reported regular thefts of their livestock. In particular, someone or something had “been making away with chickens.” Try though they might, no one could solve the crime. Was it man? Was it beast?

Then on January 4th, Eugene Collins found the chicken thief. Since so many were interested in seeing what created the mayhem, he brought the remains of the culprit into town, displaying the robber at a local drug store for all to see. Lots of people came to look at the carcass of the villain, which turned out to be an armadillo. Those that had seen the Texas variety swore the one they examined was larger than what grew down near the border. But it all made sense. Given the fact that the armadillo is famous for curling into a ball to protect itself, no one could get a fatal shot off when the creature had any kind of warning that it was being hunted.

Over the years, facts in local papers marveled at the talents of the armadillo, which was native to South America. With ninety-two teeth, it had more than any other animal, which made it a perfect predator for chickens. Reportedly, an armadillo could run faster than a man, another trait that helped it to elude even the best farmer, turned huntsman.

About three miles west of Hickory, Eugene Collins brought the armadillo to justice (read that as killed the rodent) with “a hard bony armor as a porcupine is equipped with quills.” He offered no details on how he killed his prey or ideas on how the animal got to Hickory. Collins left the speculation to his fellow farmers. With time to ‘study on it,’ they came up with two theories. The first centered around a carnival that came through town the previous fall. Folks remembered “two armadillos displayed for the benefit of the curious.” Perhaps one of them escaped and wandered the area in search of food, which it found in various Hickory chicken coops. The other possibility centered around boxcars of cotton that were shipped through the upper south. Some surmised that an armadillo could have “crawled” into a load of cotton, riding comfortably until it got near Hickory, where it got restless and exited the boxcar. Carnival viewers called the second theory ‘hooey,’ and many a spirited debate followed for weeks after.

No matter, once the armadillo was brought to justice, chickens could rest a little easier, at least until a farmer came looking for them with an ax and a hungry look in his eye. A few years later, another armadillo was found down east of Raleigh. After capture, that one was taken to the museum in the state capital for display. No word on what eventually happened to the Hickory armadillo.