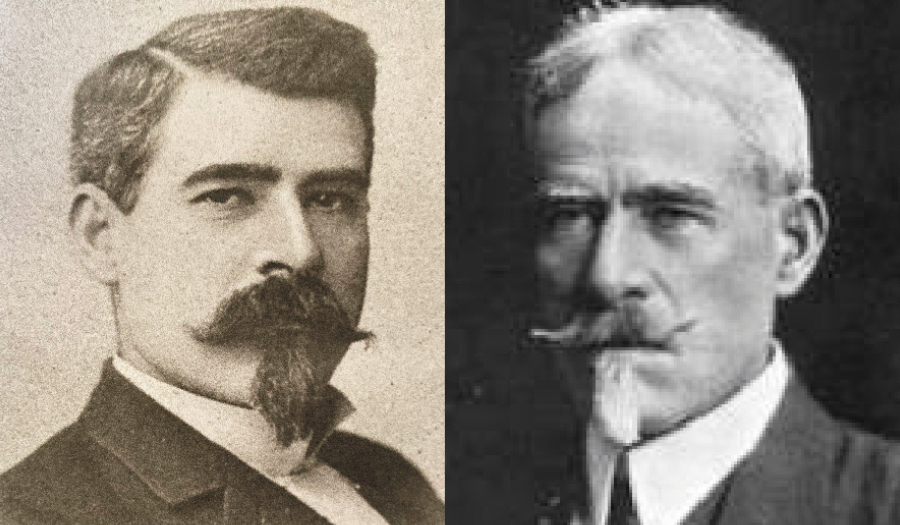

A hundred years ago, Colonel Marcellus Eugene Thornton could be found haunting the streets and avenues of Hickory as one of the town’s most eccentric characters. Long after his bet of eating 30 partridges in 30 consecutive days paid off, he flirted with politics, wed Elizabeth Rutherford, then settled into a whispered reputation as a ‘kept man’ after her money paid for the former home of D.W. Shuler, now known as Harper House.

Yet, he had aspirations of his own. Supposedly, he wrote a novel in his 20s, while working as a journalist for the Atlanta Constitution. Problem was his title, Sylvester Lester was also the name of a printer in the city who objected to Thornton’s use. Mr. Lester threatened violence. The book was never published.

After their union, the Colonel and Elizabeth made a great team. Together, they turned a Kentucky coal mine into a bonanza of a business, netting them several times the money they invested.

When he got to Hickory, the Rutherford money (and there was a lot of it) and the coal proceeds allowed him the opportunity to buy the local newspaper, the Hickory Press & Carolinian. He ran that for about three years until he decided that it was time to write a novel that would indeed see the light of day. In the Queen Anne House, up on the rise that overlooked the city, he sat down and got to work.

In 1899, he penned My Budie and I, followed two years later by The Lady of New Orleans. Both are literature of their time, pot-boilers that follow the lives of young men that the Colonel could see himself leading. In the first, the lead character is a dashing male who just happens to own a coal mine, like Marcellus himself. He rambles through Hickory and Hiddenite, discovering gems, both mineral and human as he looks for love. Both are relics of their time, complete with harsh, stereotypical portrayals regarding race and gender, but the works gave Thornton what he wanted, a reputation as a novelist.

Thornton spent the rest of his life in Hickory. Through lawsuits over land that even included ownership of a part downtown Natchez, Mississippi (he and Elizabeth charged they owned the city park), his ego never allowed him to acknowledge that marrying well allowed him to live in a style to which he had grown accustomed. It wasn’t until the death of Elizabeth, who was 18 years his senior, that the news come out that. At the time of their marriage, she had forced him to sign a prenup.

The will and testament of Elizabeth Thornton made news in town. When she died, her latest will (and she was known to have changed it regularly) named a stepson from her first marriage as executor. The colonel, he got $50 a month. He also got some of the furniture from the house and books but was forced to move out. Humiliated but publicly undaunted, he moved into a much smaller abode in town that he liked to call Thornton’s Castle. In the evenings, after imbibing his share of intoxicants (NC was supposedly dry in those days) he was reported to say that he found his way home by following the light of his cigar in front of him.

In his time, Col. M.E. Thornton was a lot of things: a lawyer, a newspaperman, a politician, a businessman, a bureaucrat, a fiction writer, he was even called “Lord Thornton” in one lawsuit. More aptly, he was a bon-vivant (pleasure seeker, hedonist) who gave Hickory one of its most vivid characters, better than anything he ever created in his novels.

Photo: Hickory’s novelist, Colonel Marcellus Eugene Thornton.