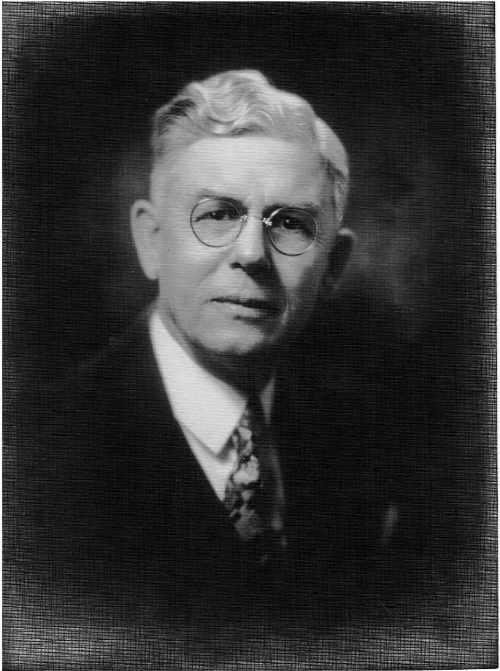

George Hall, father of Hickory Furniture. He rewarded Jim Jones for his loyal service to the company with a full wedding on the company lawn and new bed for Jones and his bride.

A wedding took place in Hickory. Jim Jones married Mary Jackson. Wearing at hat that was reportedly “two feet high,” Jim was elated as his fiancé was “arrayed in white from head to toe.” Reportedly, “both were very happy.” What made the nuptials unique was the fact that it was taking place at a furniture factory, Hickory Furniture, over in the Highland area.

After ten years of employment at Hickory Furniture, Jim Jones had become a respected employee of Hickory’s first furniture manufacturing establishment. To thank him for his exemplary service, the company enticed him to hold the ceremony on the front lawn of the company. The management also supplied the newlyweds with a brand new bed. Owner of the firm George Hall (the father of furniture in Hickory) said the wedding was “interesting all the way through.”

One detail that made the vow exchange such an event that fall Saturday afternoon in 1915 was that Jim Jones was from the African-American community in Hickory. In a time and region raging with Jim Crow segregation and racial segregation, the event said something about Hickory that could not be said of other towns in the South.

Over at Hickory Chair, just across the railroad sidetracks and a few years later, a different racial event was brewing. By 1918, the United States was at war with Germany. Some men had left Hickory to fight in the Great War (WWI) while others were in the shops providing war material. On the factory floor both black and white workers were keeping the saws running. However, labor had become scarce. In fairness, company officials decided to pay everyone the same wage for their work.

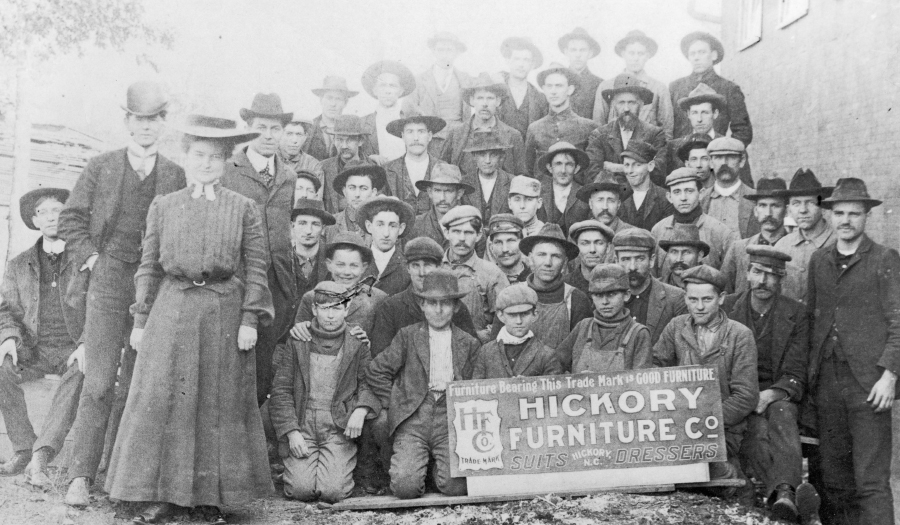

A portion of Hickory Chair workers during the company’s first decade of operation. The company employed African-American workers also but they were absent in the company photo.

The move angered white workers, who argued that they should be paid more. A group of around 60 whites demanded a ten percent increase to their pay. With the same kind of respect Hickory Furniture showed to Jim Jones, management at Hickory Chair said no to the demand. Leaders pointed out the “acute” shortage of workers and told those that were disgruntled that the situation could not be helped. The company valued the contribution of the black workers enough to stand by them when some believed that their race was enough to merit privilege. The white workers stayed on the job.

The two stories about life in the factory offer a glimpse into race relations of one hundred years ago. While some workers resented others, it was the leadership that sought to set the tone for how workers would be regarded. Racism was (and is) counterproductive. These incidents do not suggest that black furniture workers enjoyed parity on the shop floor. African-American employees were assigned to some of the toughest, dirtiest jobs in the factory, then and afterward. But the culture in Hickory was far ahead of other places in the South. Had it been another state, deeper in Dixie, in all likelihood, neither of these two events would have ever resulted.