In 1909, the automobile was still a fairly new phenomenon. Folks who were either too old to accept or too afraid of a running engine decided the new technology was not for them. If we live long enough, we will all face a new trend/innovation/discovery that we cannot abide. You see it in musicL tastes, as an example, all the time.

In a town not too far from here lived two men at odds with each other over the value of an automobile. Charlie Walker grew up in a world that operated perfectly fine without the noisy contraptions. He “entertained a grudge against automobiles,” although his anger was really vented on one particular car, which was driven by a fellow named Rush Thompson.

In a town not too far from here lived two men at odds with each other over the value of an automobile. Charlie Walker grew up in a world that operated perfectly fine without the noisy contraptions. He “entertained a grudge against automobiles,” although his anger was really vented on one particular car, which was driven by a fellow named Rush Thompson.

Walker v. Rush, as perfectly symbolic as these names are (i.e. a Walker hates the speed of cars, while a Rush embraces them, in a hurry to get where he’s going) this story is not an allegory. It was documented in the pages of newspapers across the state.

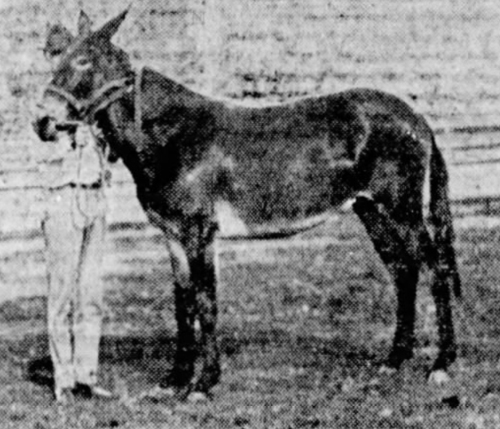

What Charlie Walker really despised was how fast the “automobilist” whizzed past him. One day Rush Thompson was driving a doctor and his family out of town past where Charlie and his mule were plowing. The animal bucked at the roar of “the Machine.” It took Charlie some doing but he finally calmed down his mule. However, Charlie Walker had reached his breaking point.

Charlie spotted the car coming back toward town as his mule was harnessed to pull his buggy, Charlie’s preferred mode of transportation. Walker was headed in the opposite direction from the oncoming car. Angered by what had taken place earlier, he decided upon a showdown. Walker pulled his mule and buggy across the road to prevent Rush Thompson from passing. The car stopped. Though Rush told the older man he would make room for him to move on past, Charlie refused, instead raising a gun in his hand and aiming it at the auto.

This could have been a story about a man willing to kill his neighbor just because he didn’t like the new technology. In court, Charlie Walker might have pled inconvenience, or provocation since the car disturbed his mule earlier, or maybe temporary insanity. But even in its early days, shooting someone because the noise had bothered your mule was not a winnable case. Charlie would likely have been convicted of murdering whomever he shot.

This could have been a story about a man willing to kill his neighbor just because he didn’t like the new technology. In court, Charlie Walker might have pled inconvenience, or provocation since the car disturbed his mule earlier, or maybe temporary insanity. But even in its early days, shooting someone because the noise had bothered your mule was not a winnable case. Charlie would likely have been convicted of murdering whomever he shot.

However, a different outcome was in the offing. As Charlie raised his gun, “he fell in his tracks and without a struggle died.” The doctor in the car rushed to the man lying facedown in the road but there was nothing that could be done for Charlie Walker. The doctor determined that the cause was “heart trouble.” What makes this story even stranger is the fact that by all accounts, Walker was known as a “quiet, well behaved citizen.”

The conclusion to this story sounds like what my colleague, English professor Robert Canipe calls a Deus Ex Machina ending, literally meaning “God in the Machine” where a miracle happens to bring about a different ending. At the critical moment an unlikely event comes along. As a plot device, it’s pretty thin, but as documentable history, the outcome offers a weird lesson. If you think about it, Charlie Walker was so mad that a heart attack isn’t so outlandish at all. He was obviously angered to the point of being ruled by his passion, only to have that passion turn against him.

The conclusion to this story sounds like what my colleague, English professor Robert Canipe calls a Deus Ex Machina ending, literally meaning “God in the Machine” where a miracle happens to bring about a different ending. At the critical moment an unlikely event comes along. As a plot device, it’s pretty thin, but as documentable history, the outcome offers a weird lesson. If you think about it, Charlie Walker was so mad that a heart attack isn’t so outlandish at all. He was obviously angered to the point of being ruled by his passion, only to have that passion turn against him.

Here is a case that tells us two things. One, the act of hating is worst that the thing you hate. Two, time and technology marches along with or without you. Oh and one more. The road is big enough for both a mule and a car.

Photos: The culture war of 1908; embrace the new fangled automobile or stay with a trusted stead. Not only will a mule get you to where you are going, it will plow your field for you too.