It’s not what we would think of as home furnishings, but for a while in western North Carolina, a handful of piano companies either started up or came here to be part of the furniture industry. Out of 18 firms in the United States in the 1960s, reportedly four of them dotted the Catawba Valley landscape. One was in Black Mountain and documentation on it is virtually nonexistent. But the other three tell a collective tale about the high and low notes of making pianos in the foothills.

Each of the three liked this region for two reasons; lots of hardwoods and skilled workers who knew how to craft a piece of furniture. It’s a bit hard to say which was more important. We start with the one that still has a standing (though abandon) factory.

Kohler and Campbell Piano Company began when a machinist and a businessman got together in New York City in 1896 and decided to partner. They were incredibly successful from the start. Soon, they began buying up other companies, including one that dated back to 1789. K&C made some 60 different models, but their best seller was one you didn’t have to play at all. It was called a player piano. A mechanism inside, referred to as the “action” used paper rolls with holes punched in them to pick out a tune. Either in their own models or supplying other makers, K&C sold 50,000 actions every year. A good business.

In 1954, the second generation of ownership found the their factory in the Bronx too crowded. Their two story building did not fit with the spread-out way they wanted to construct their musical instruments. So they came south. Finding a 12 acre tract along the rail line in Caldwell County, they constructed a facility just north of Granite Falls. Julius A. White, president of the company made the move one of his last official acts before turning the company over to his son Charles Kohler White, grandson of one of the founders.

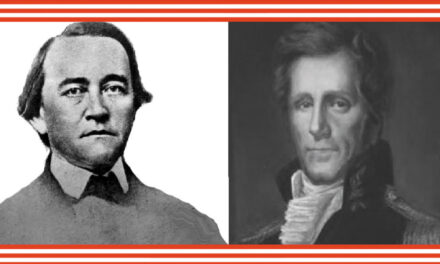

The younger White took over but his time was short. For reasons that remain mysterious, he fell to his death from the window of his 13th floor room at the Conrad Hilton Hotel in Chicago. The only way he could be identified was the wedding ring he was wearing at the time of the plunge, which had his initials and those of his wife. Otherwise, he was naked. All they found in his room was a small “grip,” the slang of an earlier era for a suitcase.

What happened? One account termed it “an accident.” No one ever figured out why 32-year-old Charles Kohler White dived through an open window on a business trip to Chicago.

The factory back in Granite Falls continued to hum for another 30 years. Six times it expanded until in 1986, the company sold out to a California firm who then sold the name to a Korean company, where Kohler and Campbell pianos are still made. The plant closed down and 200 people were out of work. That’s just one of the piano  plants that came…and went.

plants that came…and went.

If you drive up 321-A today you can still see the factory, deserted though it is. In the late 1980s, Kincaid Furniture tried to buy the complex, but the deal never went through. Reports of a contaminated well may have been a factor. You can still see the script of the company logo on the water tower that served the plant. Time has worn away much of the grandeur of the plant that shipped a record 16,000 pianos to customers in 1979.

It seems odd that a piano factory would come all the way down from NYC to a location that, by comparison was so remote. However, they were not the only ones seeking to make music in the foothills.

Photo: (Left) Caption: Charles Kohler White, the heir apparent at his grandfather’s company until his mysterious death.

(Above) The modern, 1956 Kohler and Campbell Piano plant as it looks today